Read about our update schedules here.

Composable solutions adjust quickly and with greater stability. A system architected to be composable is built in meaningful units, or building blocks, that can operate gracefully with one another and can be easily swapped in and out of service. Building composability into a system enables you to introduce new features or remove technical debt by refactoring or reassembling individual units of a system. Composability enables faster, more predictable delivery cycles and releases, as teams can focus on building and delivering meaningful features via smaller amounts of change.

Composable systems make it possible for businesses to adapt more quickly and with greater stability — whether the stimulus is internal to the business or caused by external factors. Composability helps systems be more resilient and can help make solutions and architectural patterns more intentional.

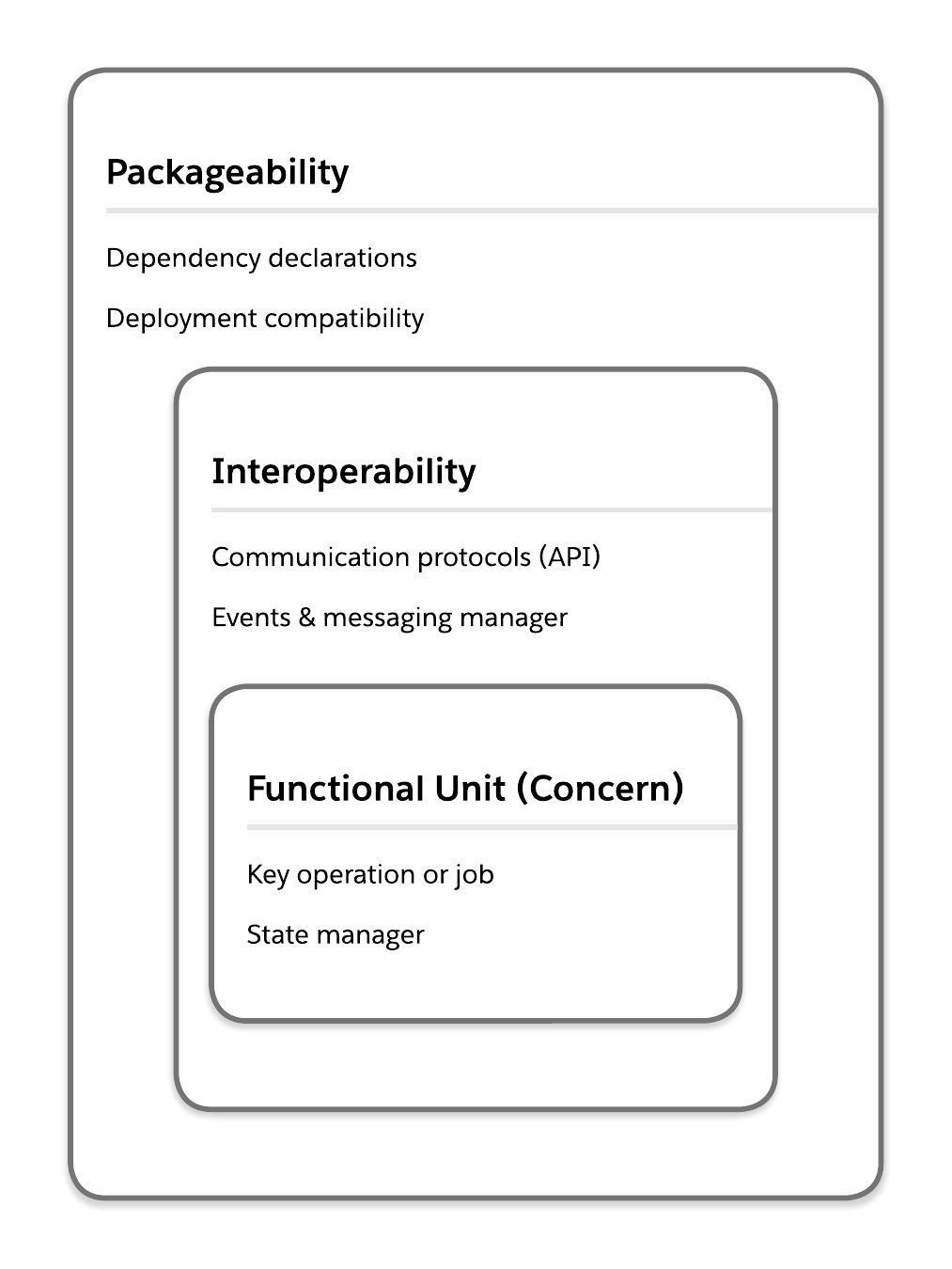

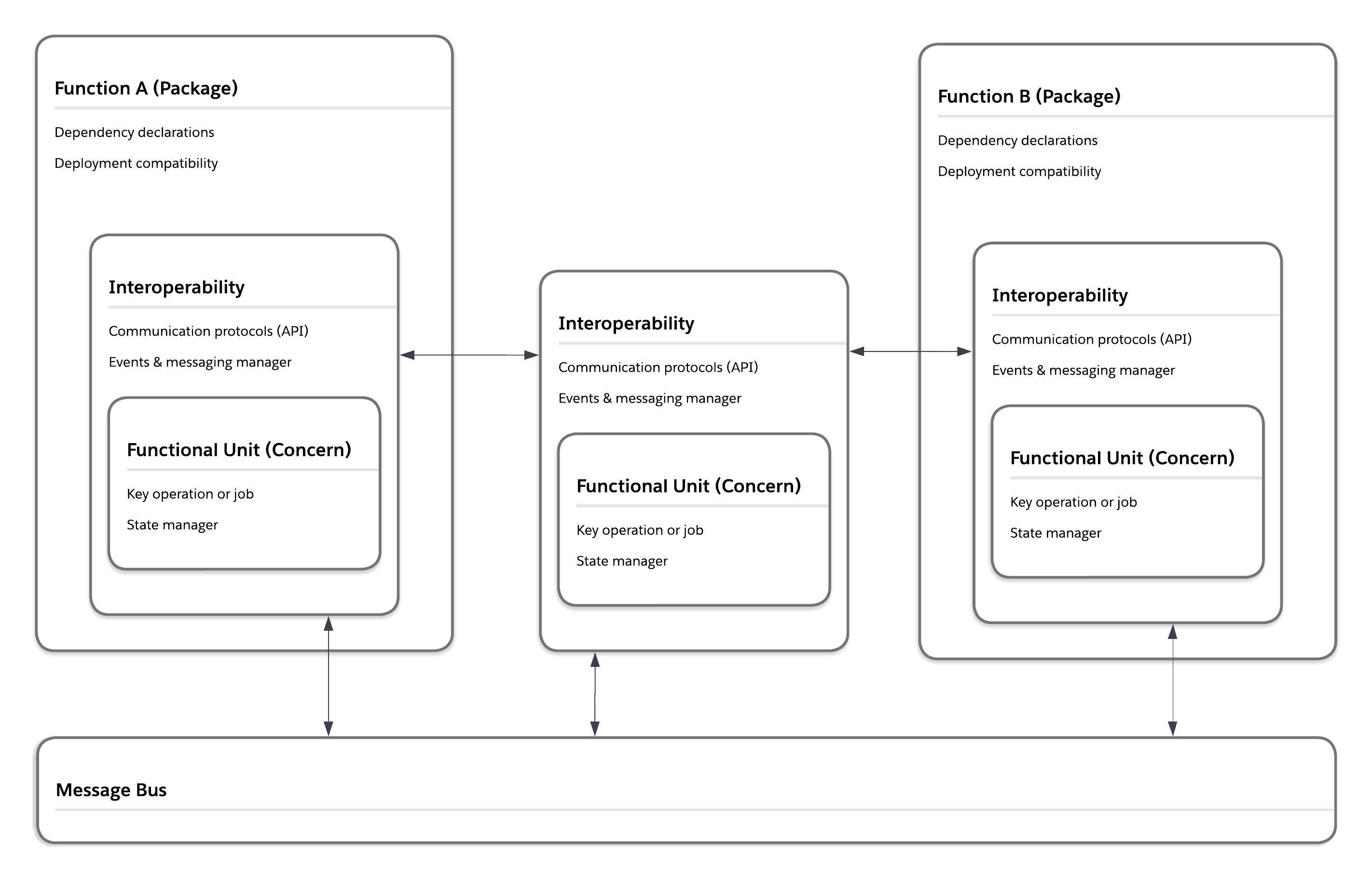

You can make your Salesforce solutions more composable by building three key habits: separation of concerns, interoperability, and packageability. Below, you can see the relationship of these habits in two ways: for a single unit of in a composable system, and across multiple units in a composable system.

A single, composable unit:

A composable system:

A fundamental concept in software engineering and system architecture, separation of concerns entails identifying various concerns within a larger system that can be separated into modular units. Achieving a strong separation of concerns within a system requires the creation of meaningful units for application logic and functions throughout the system. Smaller units make it easier for app delivery and maintenance teams to understand how and where to make changes, with minimal disruption to the larger system. Smaller units also make it clearer how and where to focus work when addressing technical debt and contribute to the overall readability of your system.

You can build better separation of concerns into your Salesforce org by orienting to business capability and managing state.

For Salesforce systems, the best approach for separation of concerns applies a business-oriented perspective to identify and organize modular units (or capabilities) within the system. This is unlike an engineering-focused view, which identifies units based on their technical function. A business-oriented perspective in separation of concerns requires organizing the code and customizations in your system based on the service they provide to the business and business users. Taking this approach does not mean ignoring potential for redundant or duplicative technical functions in a system. Rather, it means that technical services are clearly mapped to an organizing principle that is ultimately transparent to the business.

Orienting to business capabilities helps ensure that the hand-offs between business analysis and discovery teams to delivery teams are as straightforward as possible. If app builders have no idea where their work units map into your composable architecture, you have a mess, not a composable app landscape. Unclear mappings between the end state required by the business and the modular units within an org also increase the chances of development teams or vendors building redundant functions into the system.

Consider the following to orient functional units to business capability:

- Start with jobs to be done. Focus on the jobs to be done (JTBD) of users and the business itself. Pioneered by Tony Ulwick, the JTBD approach centers on understanding the “job,” or true purpose, that people are trying to accomplish by using a product or service. It’s a higher level of abstraction than users’ role-related tasks or the individual steps in a business process. For example, tasks like duplicate checks and address validations might fall into a higher-order function of “establish a single view of the customer.” After you have a clear sense of these higher-order business capabilities, you can begin to map parts of your system to them.

- Orient to capabilities, not reporting structures. The internal hierarchy of your business units are not a proxy for meaningful capabilities or jobs to be done. The internal hierarchy of your business does have material impact on processes and team structures (not to mention budgets). Those are important logistical considerations. But the functional needs of the business operate at a higher level of abstraction than logistics. If you are creating a module to serve a reporting structure instead of a higher-order function, be aware that you may have to take additional steps to identify how that module relates to business capabilities.

- Be iterative. Start by partnering with the business to identify what capability could work for a minimum viable product (MVP). When you identify a capability, start building that MVP. As you build, identify the processes, metadata, and events or messages that are central to the functional unit you are creating. Identify any processes, metadata, and events or messages that are external dependencies. As more functional units are designed, implement API management and dependency management to build units that work well with one another (instead of building siloed units).

The list of patterns and anti-patterns below shows what proper (and poor) orientation to business function looks like within a Salesforce solution. You can use these to validate your designs before you build, or identify areas of your system that need to be refactored.

To learn more about tools available from Salesforce to help you better orient to business capabilities, see Tools Relevant to Composable.

State management centers on movement of information throughout a system at various points in time. Effective state management enables applications to handle complex flows of data or interactions with a minimum of unplanned or indeterminate outcomes. Managing state in a modular Salesforce org means building clear paths for logic flows within and between units, as well as graceful paths for unplanned execution behaviors. State management makes it possible to form coherent streams of logic from modular Salesforce application units. In most cases, this requires interoperability to structure information flow between units.

Difficulties in managing state across loosely coupled units often lead to monolithic application development in Salesforce. You can see this in large “monoflows", which are built in an attempt to orchestrate a complex process within a singular flow. Another example is massive Apex classes, which orchestrate complex processes through spaghetti code, or a lengthy series of single-use methods. These types of application architectures make refactoring and debugging difficult and increase onboarding times for new team members or vendors. They also reduce the value of the applications delivered to the business, as functionality isn’t reusable.

Consider the following to manage state across a modular Salesforce org:

- Decide on when to use stateful versus stateless patterns. Stateful patterns retain information throughout an execution path, stateless patterns do not. In a loosely coupled system, stateless patterns make it possible for components to be refactored more quickly and with fewer side effects. However, stateless patterns are not appropriate for all use cases. If you are building components for data operations, stateful patterns can help with data integrity and consistency throughout your systems. Use a stateful pattern if your component meets any of the following criteria:

- Awareness of placement within a greater execution path is essential to the component’s behavior

- The behavior of the component needs to change based on the results of a downstream action (for example, it needs to change execution based on rollback/error/success messages from downstream components)

- The component needs to wait for responses from an external or downstream system to finish its work

- Create meaningful categories for stateful information. State is an ambiguous term that can be applied to such a deep and wide array of information within (and beyond) a Salesforce org that by itself the term is almost meaningless. A necessary first step to building stateful patterns, therefore, is creating meaningful categories for the most important stateful execution paths (or kinds of stateful behaviors) within your system. Some categories to consider:

- Navigation and forms

- Database operations

- Batch and bulk operations

- Errors

- Define data-related states in terms of database transactions. The built-in behaviors of the platform will circumscribe the majority of state considerations for data in Salesforce. Don’t try to manage against or around this behavior. Design for and with it. Design solutions that minimize, or eliminate, distributed transaction logic. (See data handling for more details).

- Identify states that occur within (and across) functional units. As you assemble functional units into larger systems, be aware of when you’re mixing stateless and stateful component behavior, and prevent combinations that might create endless loops or gaps in processing.

- Define hand-offs. Consider what messaging or eventing patterns components will use to transmit state-related data to another part of the system. Ensure you are building transaction awareness and handling into your components. Do not include any distributed transaction logic in your hand-offs.

- Create mappings between your process diagrams and states. Process diagrams detail the steps that move information through your system at various points in time. A state diagram shows the actual changes in the information (the state). Use the metadata footer portion of the Salesforce Diagrams shapes to capture the changing state of information within each step of your process. If you separate process diagrams and state diagrams, be sure to link them. This concept should not be confused with capturing current and future state of processes or system landscapes during design and implementation, as that is not about the information moving through the system.

The list of patterns and anti-patterns below shows what proper (and poor) state management looks like within a Salesforce solution. You can use these to validate your designs before you build, or identify places in your system that need to be refactored.

To learn more about Salesforce tools for managing state, see Tools Relevant to Composable.

The following table shows a selection of patterns to look for (or build) in your org and anti-patterns to avoid or target for remediation.

✨ Discover more patterns for separation of concerns in the Pattern & Anti-Pattern Explorer.

| Patterns | Anti-Patterns | |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Units | In your design standards:

- Naming conventions address how to denote a functional unit - A list of all currently defined functional units (and related naming conventions) exists - Standards for proposing functional unit additions or changes exist |

In your design standards:

- Design standards do not exist or do not deal with functional units and use cases |

| In your documentation:

- System landscape diagrams clearly show the functional units in an org - All documentation and implementation diagrams clearly show the functional unit(s) for components - Documentation for individual components include functional unit mapping for the component - All components within a functional unit are searchable and easy to find |

In your documentation:

- Component documentation does not exist - Component documentation describes the functional unit a component belongs to, but that is the only place the definition of that functional unit appears - You cannot search for a particular functional unit and/or searches do not help identify all the components within a functional unit |

|

| In your org:

- It is possible to quickly identify functional unit alignment for a given piece of metadata (for example, a flow, Apex class, or Lightning page) - Functional units are labelled in business-friendly terms |

In your org:

- It is not possible to identify functional unit alignment for any metadata - Functional unit information is inconsistent or inaccurate - Functional unit information is labelled in engineering-focused terms that are meaningless to business users |

|

| State Management | In your design standards:

- Use cases for stateful vs. stateless designs are clear - Approved patterns for stateless communication exist - Approved patterns for stateful communication exist - Clear categories for state exist |

In your design standards:

- Design standards do not exist or do not deal with state/stateless patterns and use cases |

| In your documentation:

- Every component that handles stateful and/or stateless communication indicates what pattern has been implemented - It is possible to search for and find all components that have implemented a particular stateful/stateless pattern - Process and interaction diagrams provide detail about state categories and hand-offs |

In your documentation:

- Component documentation does not exist - Component documentation describes the stateful/stateless pattern implemented, but that is the only place the definition appears - It is not possible to search for a particular pattern and/or searches do not help identify all the components using that pattern |

|

| In Apex: - Savepoints and rollback behaviors are used in all data operations |

In Apex: - Savepoints and rollback behaviors are not used |

|

| In Flow: - Fault paths and the Roll Back Records element is used |

In Flow: - The Roll Back Records element is not used |

In a system architected for interoperability, components can exchange information and operate together effectively. Interoperability is a key to making a modular system composable rather than siloed. Interoperability can be difficult to achieve in a loosely coupled system. You need to establish standards for consistent methods of integration that don’t undermine the independence between units and overall separation of concerns across the system.

Interoperability also impacts the quality of your user experiences. Your users expect data created in one area (like order information) to be usable in another (like marketing campaigns), and your builders expect that if they learn how to do something (like build a flow, or authenticate to an API) that they’ll find familiar techniques work when they move on to the next problem. Failing to design for interoperability will result in redundant architectures, replicated data, process inefficiencies, and increased development and support costs.

You can create interoperability in modular systems with messaging and eventing as well as with API management.

Messages and events are two ways you can enable components across a system to send and receive information. In terms of the content they can carry, events and messages are similar. A key difference is the behavior of the sender. A component sending a message typically sends data to a specific destination, and awaits some kind of response from the recipient. In contrast, a component emits an event when something has happened. There is no specific destination, nor an expectation of a response. These differences in behavior support different communication patterns. Messages support stateful communication patterns, and events support stateless communication patterns. (See State Management for more about this distinction.)

It’s important to align teams on protocols and use cases for messaging and eventing. Unclear standards can result in a mix of patterns across your system, leading to:

- Performance and scalability issues where the wrong patterns are applied to a specific use case

- Inconsistent processing that makes the system appear unstable to end users

- Longer troubleshooting times and more complex maintenance processes

Consider the following when designing messages and events to create more loosely coupled structures within your Salesforce org:

- Identify sync and async use cases. Eventing allows for loosely coupled, stateless, and asynchronous communications across a system. Messaging allows for more tightly controlled, stateful, and synchronous patterns of communication. When deciding when to use messages or events, you need to decide if your communication needs to be synchronous (and potentially blocking) versus asynchronous and non-blocking.

- Define data structures carefully. The structure of the information that components pass between them is an important part of keeping a loosely coupled system manageable and coherent. (See API Management for more on this.) A key consideration when designing a message or event is how often the structure of the information may need to change. Once a message or event structure is defined and implemented in your system, it can be difficult to handle updates — especially if the event or message is already being used to send information to an external system.

- Right-size messages. In general, it is a best practice to keep message sizes small. However, there is also a balancing act between message size and message volume. Systems can process smaller amounts of data more quickly. The act of processing comes with an amount of additional overhead as recipients have to unpack, interpret, and determine what to do with information they’ve received. These steps may take a negligible amount of time to complete, but they can build up and create a burden on systems at scale. Avoid designs that require components in the system to process many small messages in succession to complete a piece of work. To right-size your messages, think about designing for the minimum data downstream components will need to successfully process and act on information they’ve been sent, without also assuming every downstream component will be capable of requesting or processing numerous follow-on messages.

- Design for scalability. Loosely coupled components can make it easier to scale your architecture. Eliminating cross-component dependencies enables teams to work on improving performance or scalability of any individual component with minimal effects on the others. However, loosely coupled components also introduce significant complexity into your architecture at scale (especially when it comes to managing state). Identify processes that need to have more tightly coupled logic or dependencies for valid user experience or data integrity reasons — and don’t attempt to introduce async/event-based patterns into those processes. Use sync/message-based patterns and proper error handling instead.

The list of patterns and anti-patterns below shows what proper (and poor) messaging and eventing looks like within a Salesforce solution. You can use these to validate your designs before you build, or identify places in your system that need to be refactored.

To learn more about Salesforce messaging and eventing tools,see Tools Relevant to Composable. For more on choosing an eventing pattern or tool for a given use case, see the Architect’s Guide to Event-Driven Architecture with Salesforce.

Building proper application programming interface (API) management within a Salesforce solution enables individual components of your system follow predictable communication patterns. Salesforce provides built-in, secure APIs to use for communication with systems outside Salesforce. (For more on Salesforce Platform APIs see Architecture Basics.)

Effective API management within Salesforce solutions is key to building truly composable architectures. It enables components inside a Salesforce org to send and receive information efficiently. It also enables solution builders to follow clear protocols for how the components they build communicate with other components in the system, and helps them identify poor implementations early. Further, it enables solution builders to more narrowly focus on the particular component they are building or refactoring, which boosts productivity and quality.

API Management at the enterprise level is a separate topic — and is best achieved with a comprehensive API Management tool. (For more on the MuleSoft perspective on this topic, see What is API Management?.)

Consider the following to build API management capabilities within your Salesforce solutions:

-

Think of APIs as predictable patterns or contracts for communication. The data type of input or output variables, variable names, the pieces of information that should (or should not) appear in a given pattern — these are the keys to effective API management. These definitions should appear in your design standards, and teams should be able to find out how these definitions have been implemented in particular parts of your system via your documentation. One way to view difficulties merging changes from new development into an integration environment is to look at them as evidence of where you have poorly implemented API communications (or perhaps no API definition at all).

-

Don’t limit your thinking on APIs to code exclusively. What defines an API in this context is the consistency of the message structures and variables within that message. As long as that consistency is maintained, an API can be implemented in code as well as in declarative customizations, such as modular autolaunched (or platform event-triggered) flows, or even flow templates. Base your decisions around what to define in code versus in flows not on API implementation but rather on packageablility and testability.

-

Keep your lifecycle and versioning simple. Like all parts of application development, APIs have a lifecycle: define, build, test, deploy, and maintain (including retire). Salesforce Platform APIs release several versions within a calendar year, because of the platform’s rapid release cycle. (You can read more about this behavior in Salesforce Architecture Basics.) This means that platform APIs have a fairly complex lifecycle, as several versions of a particular API need to be maintained and available for Salesforce customers. This level of complexity is appropriate for PaaS use cases — but it is most likely unnecessary complexity for your on-platform solution architectures (see: Readablility anti-patterns). Focus on defining a clear purpose for an API (for example, error handling) and clear baseline definitions. Aim to have only one version of each API.

-

Make your APIs discoverable, accessible, and manageable. Document your APIs so potential consumers can find available APIs connect to them easily. APIs need to function smoothly as part of a landscape of capabilities.

-

Be iterative. Focus on defining and implementing only one internal API at a time. That way, you can focus on iterating the API definition rapidly, find the right form for your one supported version and establish best practices from the experience of implementation.

The list of patterns and anti-patterns below shows what proper (and poor) API management looks like within a Salesforce solution. You can use these to validate your designs before you build, or identify areas of your system that need to be refactored.

To learn more about tools available from Salesforce to help you build more interoperability, see Tools Relevant to Composable.

The following table shows a selection of patterns to look for (or build) in your org and anti-patterns to avoid or target for remediation.

✨ Discover more patterns for interoperability in the Pattern & Anti-Pattern Explorer.

| Patterns | Anti-Patterns | |

|---|---|---|

| Messaging and Eventing | In your design standards:

- Clear standards exist for when to use synchronous patterns (messaging) and asynchronous patterns (eventing) - Clear standards exist for event and message structures |

In your design standards:

- Design standards do not exist, or they lack clear standards for sync vs. async patterns and clear standards for message or event structures |

| In your org:

- Platform events used for internal system messaging are clearly labelled - Salesforce Flow tools reference system-wide messaging or eventing services - Consistent messaging and eventing patterns appear in flows and code |

In your org:

- Platform events used for internal system messaging are not clearly labelled or do not exist - Different strategies for messaging and eventing patterns appear across flow and code |

|

| In Apex or LWC:

- Custom event definitions are limited in scope (no system-wide events or messages are defined in code) - System-wide messaging or eventing services in Apex are annotated in ways that make them available in Salesforce Flow tools |

In Apex or LWC:

- System-wide message and/or event structures are defined in Apex or JavaScript - System-wide event or message structures defined in Apex are not available in tools like flow |

|

| API Management | In your design standards:

- Clear protocols for cross-component communication (i.e. APIs) exist - Protocols/APIs are outlined in logical groups that builders can search for and find - Protocols/APIs define variable data types, variable names, what is required or optional and provide a clear description of when to use |

In your design standards:

- Design standards do not exist or do not define APIs and use cases |

| In your documentation:

- Every component's documentation clearly lists which API/communication protocol has been implemented - It is possible to search for a particular API or protocol and identify components where it is implemented |

In your documentation:

- Component documentation does not exist - Component documentation describes the API implemented within a component, but that is the only place the API definition appears - It is not possible to search for a particular API or protocol and/or searches do not help identify components where an API or protocol has been implemented |

|

| In your org:

- API message formats and variables for internal communication are defined with custom metadata types - API message formats and variables for internal communication are defined with platform events - Code and declarative customizations reference the appropriate custom metadata type (or platform event) in order to send or receive information |

In your org:

- Communication between components of the system (code and declarative customizations) is ad hoc - APIs are defined exclusively for communication between Salesforce and external systems |

Creating packageability in a Salesforce org means functionality in the org comes from units that can be developed and deployed independently and reliably, as packages. Ideally, these units are defined as a type of second-generation package (either an unlocked package or managed package for ISVs). Note: Because well-architected solutions use these package types exclusively, first-generation managed packages are not covered here.

It’s one thing to define separations of concerns and create functional units in a Salesforce org. It’s another thing to untangle and manage dependencies clearly enough to successfully version those units as package artifacts. Achieving that level of stability and metadata isolation requires a significant level of DevOps (and architectural) maturity. It also speeds up development time, improves app builder experiences, and brings predictability and control to releases and release management. Not every organization will be capable of supporting the infrastructure required to define, maintain, and develop effective packages. But achieving packageability should be the ultimate goal for nearly every Salesforce org.

You can build packageability in your Salesforce solutions by focusing on loose coupling and dependency management.

In a system with loose coupling, individual pieces are not strongly tied to one another. Many of the advantages of a composable system stem from loose coupling. In packageable systems, achieving loose coupling between packages (and installing orgs) will enable you to have well-defined packages and more productive development cycles for teams working with packages.

On the Salesforce Platform, you can build packages that are tightly coupled to a particular org. This capability is useful in defining functional units and experimenting with proper separation of concerns in your org, as you progress in packaging maturity. If you choose this approach, however, you will realize few of the benefits of truly packageable metadata, including source-driven development, the ability to use versioning, and artifact stability. Instead, you will likely continue to experience the drawbacks of a tightly coupled system, including:

- Single points of failure causing outages and performance issues

- Slow, unpredictable deployments

- Difficult, complex debugging and troubleshooting cycles

- Issues with scale and performance

The end goal for any packageable Salesforce system is loosely coupled packages.

Consider the following as you look at separating your Salesforce metadata into effective packages:

- What customizations are data versus metadata. When it comes to packageability, the Salesforce Platform treats data and metadata very differently. It is important to understand what features in your org are metadata or data. You cannot include data in any packaged units. As you decide where to begin abstracting functionality into a packaged unit, your teams will need to decide if customizations stored as data should be excluded from the package altogether or refactored into a metadata-based implementation.

- How packaging will impact teams. A logistical reality of Salesforce packaging is that much of the work of producing and releasing a package version requires skill with the Salesforce CLI and/or CI/CD technologies. This means low-code and programmatic customizations alike will require time and attention from someone capable of working with package-related DevOps technology. Depending on how your team manages feature delivery, package adoption may pose significant slowdowns or blockers to different teams across an org. You will have to identify if teams will be able to manage feature delivery via packaging, and make a plan to address any skill or staffing gaps. Solutions might include adopting paired programming or implementing CI/CD jobs for dev environments.

- How packaging will change environment strategies. In a package-driven development lifecycle, early work should be done in scratch orgs. These temporary, source-driven development environments allow for faster, more iterative cycles. They also support more granular environment access controls for your development teams and greater isolation from production. The more dependencies your packages have on unpackaged metadata or data that only exists in a sandbox or production environment, the less likely it is teams will be able to actually use scratch orgs. You can enable source tracking in sandboxes, to allow for source-driven development patterns in non-scratch org environments — but your development teams will not benefit from the speed and iterative velocity of scratch orgs.

- How package versions relate to releases. Plan for how often and at what stage of development package versioning should happen. Package version requests are limited (per org) on a 24-hour rolling basis. As a general best practice, only version a package when you are confident none of the package contents need to change. Ideally, you will provision package versions after quality assurance processes have completed. Do not allow development teams to use the success or failure of package creation requests as “tests” of how well they’ve defined package boundaries. There are ways to do this without attempting to version a package artifact.

- What the ideal end-state should support. The ideal packaging strategy allows for controlled, stable Salesforce releases that can be developed and delivered rapidly. Defining too many packages throughout your org can generate new kinds of complexities and bottlenecks for development teams. An overly modularized org can also cause releases to be slow and difficult. Start with building and releasing a few versions of a single, meaningful package. Derive follow-on packages incrementally. Stop introducing packages when you have a release cadence that serves your business well. Refactor packages over time, if business needs change or release quality declines. The ideal package end-state is subjective.

Regardless of how you decide to define your packages, you will only successfully version a loosely coupled package through effective dependency management.

The list of patterns and anti-patterns below shows what proper (and poor) loose coupling looks like for Salesforce packaging. You can use these to validate your designs before you build, or identify areas of your system that need to be refactored.

To learn more about Salesforce tools to help you build more packageability, see Tools Relevant to Composable.

In the context of a Salesforce solution, dependency management means identifying and structuring the relationships between the metadata in your packages and the metadata in the orgs into which those packages will be installed. Dependency management is a key part of developing stable package artifacts.

Dependencies can be at odds with efforts to create perfectly separated, loosely coupled functional units. In an ideal engineering state, a loosely coupled system has no dependencies between units. In the real-world, however, eliminating all dependencies is not practical.

Often, the balance between making systems readable and using business-friendly functional units requires a trade-offs in terms of perfect isolation across the units in a system. More pragmatically, the core services provided by the standard functionality of the Salesforce Platform create key, net-positive dependencies for any Salesforce solution. Many built-in scalability, performance, and security advantages come from how deeply they are integrated into the platform. When designing packageable Salesforce solutions, it’s important to remember that package dependencies are not inherently bad. Poor dependency management is bad.

Effective dependency management with Salesforce packaging means development and maintenance teams can:

- Onboard to new projects faster and with limited environment access

- Quickly develop and test changes

- Understand how complex functionality should be delivered in smaller, specific commitments

- Control release cadences, and reduce system maintenance/release outage windows

- Predictably rollback adverse changes in any environment

The techniques for dependency management with Salesforce are fairly straightforward:

- Use messaging and eventing to handle graceful hand-offs of stateful or stateless information between components.

- Use custom metadata types to provide dynamic run-time information and to support dependency injection patterns.

- Have Apex developers use abstract or virtual classes.

In the end, you will need to decide the design patterns that are allowed in your org across declarative and programmatic development. The most important considerations (architecturally) are to define where you want to add more engineering complexity in order to have fewer dependencies, and where you need to tolerate more dependencies to simplify app builder workflows.

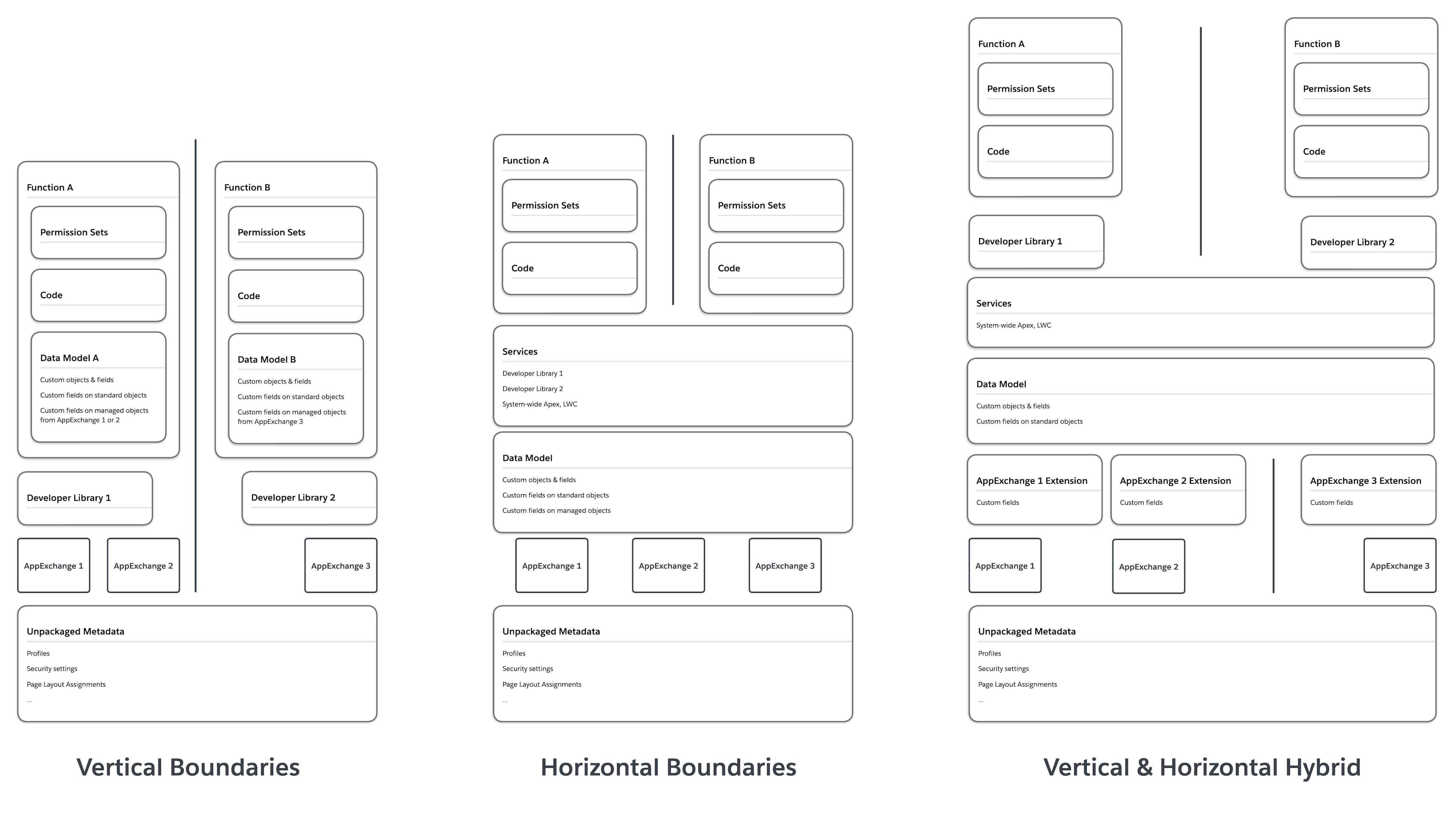

As you build dependency management strategies into your packages, consider the two primary organizing principles for package units: horizontal and vertical.

- Horizontal boundaries. In horizontal paradigms, functionality that might be needed by more than one package is abstracted into a horizontal layer. Horizontal layers then become the source of common functionality, and are accessed via a declared dependency. Minimizing redundant functionality across packages is favored over minimizing dependencies.

- Vertical boundaries. Vertical paradigms maximize isolation and loose coupling between parts of the system. Shared functionality is limited, and similar work might appear across units. Dependencies are strictly limited, in order to maximize isolation between package units.

Note that this is not an either/or decision. You can mix vertical and horizontal paradigms as needed. Often, the fastest way to start with a package is to create horizontal service layers. As the scale and complexity of your package adoption grows, abstracting more vertical units will help simplify complex environment setup processes or developer onboarding.

A system with two functional units (A and B), for example, can be structured with package dependencies arranged in vertical, horizontal, and vertical-horizontal hybrid paradigms.

Regardless of the package organizing paradigm you choose, there are some absolutes to keep in mind:

- Do not duplicate metadata across packages. Metadata needed by more than one package should be abstracted into one or more packages that are declared as dependencies.

- Make use of the built-in dependencies of Salesforce Platform metadata. For app builders, the built-in services offered by the Salesforce Platform provide a great deal of functionality that can be configured quickly. Many of these services have built-in dependencies that make them difficult to abstract into low-level functional units. For a given metadata type, you need to understand where it falls along the spectrum of built-in dependencies, and use this understanding to define your package dependency chains. Don’t start package adoption by trying force loose coupling into a piece of standard platform functionality with lots of built-in dependencies. It will add complexity (not value) as you reach higher-order capabilities. It is also another way to fall into standard vs. custom anti-patterns. Package metadata from the bottom (fewest dependencies) up — and iterate over time.

- Watch your dependency chains. Avoid creating package dependency chains that will require developers to split their changes into many different packages at any one time.

- Think about what makes sense for source control. There are two basic ways to manage your packages in source control. The first is a single monorepo with packages isolated within folders. The second is multiple repos with packages isolated in their own repos. There are complexities to managing each kind of source strategy, long-term. In terms of developer onboarding, vertical boundaries are more efficient in multiple repo paradigms. Horizontal boundaries are more comprehensible in a monorepo. Again, you can mix and match strategies as your architecture matures.

The list of patterns and anti-patterns below shows what proper (and poor) dependency management looks like with Salesforce packages. You can use these to validate your designs before you build, or identify areas of your system that need to be refactored.

To learn more about Salesforce tools for dependency management, see Tools Relevant to Composable.

The following table shows a selection of patterns to look for (or build) in your org and anti-patterns to avoid or target for remediation.

✨ Discover more patterns for packageability in the Pattern & Anti-Pattern Explorer.

| Patterns | Anti-Patterns | |

|---|---|---|

| Loose Coupling | In your design standards:

- Naming conventions address how to denote package units - It's possible to search for and find a list of all currently defined package units (and related naming conventions) - Standards for proposing package unit additions or changes exist - (Optional) All approved use cases for custom settings are clearly listed (if you have any) |

In your design standards:

- Design standards do not exist or do not deal with package units and use cases |

| In your org:

- Custom metadata types provide dynamic, run-time information for code and declarative customizations - No custom settings exist or few custom settings exist, and none are related to packaged functionality - No custom objects exist in order to provide dynamic, run-time information for code or declarative customizations |

In your org:

- Custom settings are used - Custom objects exist in order to provide dynamic, run-time information for code or declarative customizations - Custom metadata types are not used (or are not used consistently) to provide dynamic, run-time information for code and declarative customizations |

|

| In Apex:

- Common services and boilerplate code are defined using abstract or virtual Apex classes - Methods dependent on dynamic, run-time information reference appropriate custom metadata types |

In Apex:

- Common services and boilerplate code are not easily distinguished from other classes - Internal references across classes and methods are hard to follow and are inconsistent throughout the codebase - Methods do not use a consistent approach for accessing dynamic, run-time information, or methods query custom objects for runtime behavior information, or code references custom settings |

|

| In source control and development environments:

- package.xml files only appear in early stage or proof-of-concept project manifests |

In source control and development environments:

- package.xml files are used to control metadata deployments |

|

| In packages:

- Org-dependent unlocked packages are used only for early-stage or proof-of-concept experiments - No unmanaged packages are defined in production or sandboxes |

In packages:

- All packages are org-dependent unlocked packages - Unmanaged packages are defined in production or sandboxes |

|

| Dependency Management | In your design standards:

- Standards for declaring dependencies exist - Standards for introducing or modifying dependencies exist |

In your design standards:

- Design standards do not exist or do not deal with how to declare dependencies |

| In source control:

- Package versions for unlocked packages use aliasing ( LATEST) to declare dependencies in sfdx-project.json manifests

- Developers can create scratch orgs and deploy package metadata successfully from source control |

In source control:

- Package versions for unlocked packages are declared explicitly (no LATEST aliasing) in sfdx-project.json manifests

- Developers cannot work successfully with scratch orgs using source control |

|

| In your packages:

- No metadata is duplicated across packages - For package development, all early-stage development work happens in scratch orgs |

In your packages:

- Dependencies are circumvented by duplicating metadata in different packages - Early package development happens in developer sandboxes or early package development cannot happen in scratch orgs |

|

| Also see: Loose Coupling | ||

| Tool | Description | Separation of Concerns | Interoperability | Packageability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apex REST Web Services | Expose your Apex classes and methods to external applications via REST | X | ||

| Apex SOAP Web Services | Expose your Apex classes and methods to external applications via SOAP | X | ||

| Change Data Capture | Publish changes to Salesforce records | X | ||

| Custom Metadata Types | Define reusable, customizable, packageable functionality | X | ||

| Decorators | Expose functions or properties publically as an api | X | X | |

| Dev Hub | Manage scratch orgs, second-generation packages, and Einstein features. | X | X | X |

| Generic Events (Legacy)* | Send custom events that are not tied to Salesforce data changes | X | ||

| Lightning Data Service | Cache and share data across components | X | X | |

| Metadata API | Deploy customizations between Salesforce environments | X | ||

| Metadata Coverage Report | Determine supported metadata coverage across several channels | X | ||

| Mulesoft Composer | Build process automation for data using clicks instead of code | X | ||

| Outbound Messages | Send messages to external endpoints when field values are updated | X | ||

| Platform Events | Send secure and scalable messages that contain near real-time event data | X | ||

| Pub/Sub API | Subscribe to platform events, Change Data Capture, or Real-Time Event Monitoring | X | ||

| PushTopic Events (Legacy)* | Send and receivedata change notifications matching a user-defined SOQL query | X | ||

| Salesforce CLI | Develop and build automation when working with your Salesforce organization | X | ||

| Salesforce Diagrams | Create diagrams to show business capabilities and technical details | X | ||

| Salesforce Extensions for Visual Studio Code (Expanded) | Official VS Code extensions for Salesforce development | X | ||

| Scratch Orgs | Deploy Salesforce code and metadata to a disposable org | X | ||

| Second Generation Managed Packages | Develop and distribute apps for the AppExchange | X | ||

| Tooling API | Build custom development tools or apps for Lightning Platform applications | X | ||

| Unlocked Packages | Organize metadata, package an app, or extend an AppExchange app | X | ||

| *Salesforce will continue to support PushTopic and Generic Events within current functional capabilities, but does not plan to make further investments in this technology. | ||||

| Resource | Description | Separation of Concerns | Interoperability | Packageability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Primitive Look at Digital Integration | Develop a common language for connectivity concepts | X | ||

| Applying Domain-Driven Design with Salesforce | Orient your solutions around business capabilities | X | ||

| Best Practices for Second-Generation Packages | Understand 2GP packaging patterns and practices | X | ||

| Components Available in Managed Packages | Understand managed package metadata components | X | ||

| Design Standards Template | Create design standards for your organization | X | X | X |

| Event-Driven Architecture Decision Guide | Compare event-driven architecture patterns and tools | X | ||

| Events Anti-Patterns | Identify anti-patterns to avoid when using events | X | ||

| How to design message-driven and event-driven APIs | Read up on the differences in a MuleSoft dev guide | X | X | |

| Learn About the Jobs to be Done Framework | Explore JTBD on Trailhead | X | ||

| Manage Global State in B2C Commerce | Easily pass data between components to maintain state | X | ||

| Messaging Guidelines | Communicate relevant information and create moments of delight | X | ||

| Messaging Types | Understand different messaging types by the nature of user interaction | X | ||

| Metadata Types | Understand the different types of metadata in your Salesforce org | X | X | |

| Mobile App Notification Types | Understand notification types for Salesforce mobile apps | X | ||

| Optimizing the View State | Maintain state in a Visualforce page | X | ||

| Salesforce Developer Experience (DX) | Manage and develop apps on the Lightning Platform | X | X | X |

| Unsupported Metadata Types | Identify components that aren’t available in Metadata API | X |

Help us keep Salesforce Well-Architected relevant to you; take our survey to provide feedback on this content and tell us what you’d like to see next.