Modern Salesforce architectures are increasingly powered by asynchronous processing; not as a convenience, but as a strategic requirement for scale. In recent years, we've seen more and more companies contending with surging data volumes, complex integrations that involve multiple touchpoints, and the rise of autonomous systems running 24/7/365. All of these things push architects towards designing systems that are asynchronous-first.

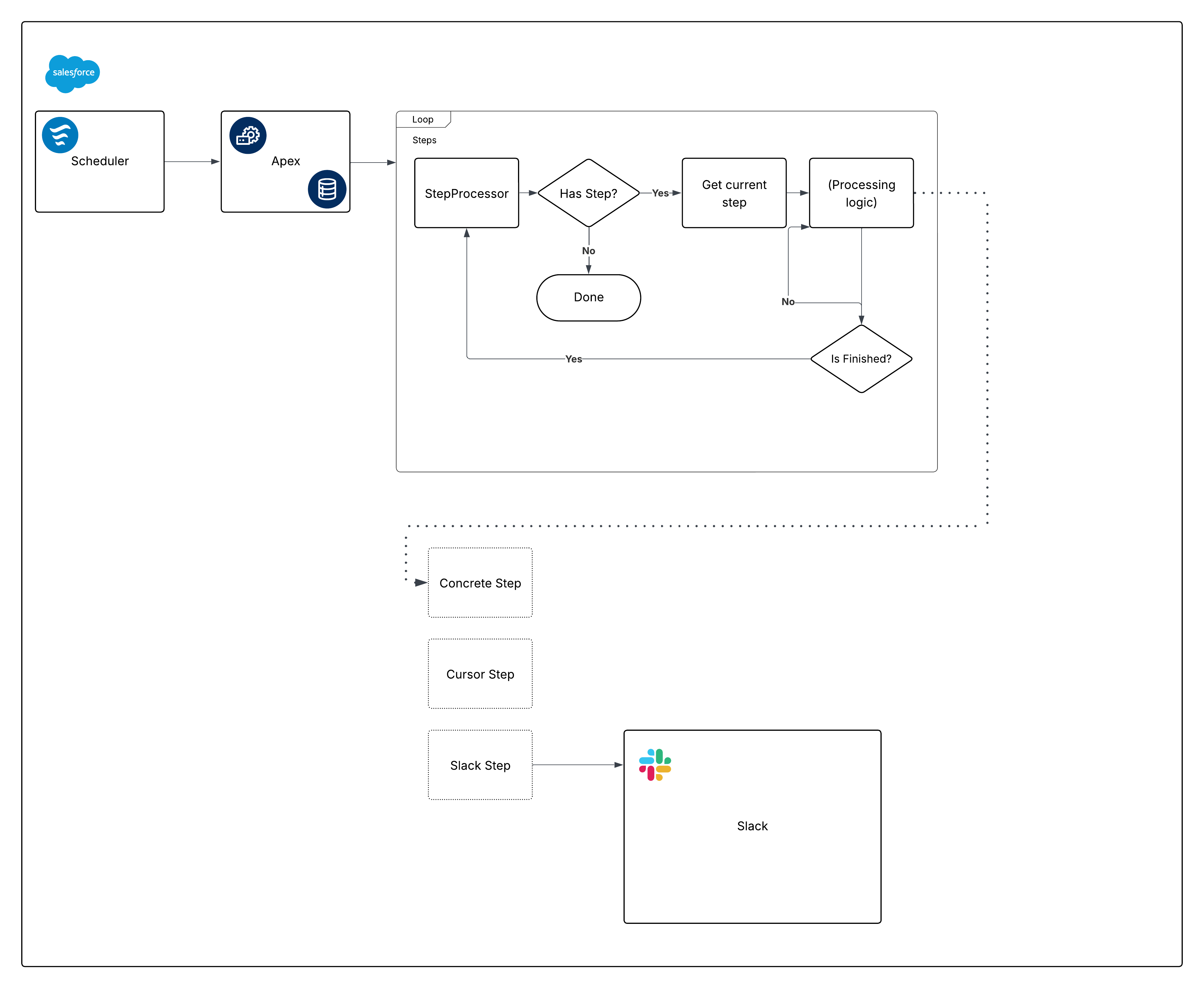

Asynchronous processing on Salesforce often means designing around governor limits and complexity. Those limits act as guardrails and architectural constraints that help produce bulk-safe, scalable systems. While no platform limits directly serve to manage complexity, design patterns can help mitigate risk on that front. Internally, Salesforce often pushes the platform’s boundaries to forward‑test new features and automate complex business processes. We built a Step-Based Asynchronous Processing Framework for running asynchronous jobs with an arbitrary number of steps. Each step can run, retry, and restart independently with shared governance controls and full operational visibility through centralized logging. This document outlines its key architectural components: Queueable Apex and Finalizers, Scheduled Flow, Apex Cursors, Invocable Actions, and integrations with Slack. Together, these components provide a modular, scalable, and observable architecture suited for evolving enterprise needs.

- Modern Salesforce architectures should embrace an asynchronous-first approach to achieve scale, resiliency, and operational transparency.

- Breaking complex work into independently executable steps enables predictable performance, safer retries, checkpointing, rollback, and modular evolution without re-engineering core workflows.

- The framework provides a scalable alternative to monolithic and aging batch jobs, chained async calls, and deeply nested flows, and is built for high-volume workloads that must scale horizontally inside Salesforce without off-platform orchestration.

- Deterministic and observable execution ensures progress tracking, SLA monitoring, failure diagnostics, and audit-level transparency through centralized logging and governance.

- Designed for enterprise-grade rigor, including unified governance, compliance, and distributed state control across long-running business processes.

Before reviewing the requirements, here are some dos and don’ts for when to use a framework like this. Above all, consider which system is the single source of truth. If your Salesforce org relies minimally on external data but needs to scale from hundreds to millions of records, consider a step‑based async framework.

Do use this framework if:

- Most (or all) of the information to act upon already exists in your CRM.

- The upfront or ongoing cost of maintaining an Extract Transform Load (ETL) job to harmonize external data is too high.

- You need to defer processing a large number of Salesforce records on a set schedule.

- You can break down the processing into discrete steps. For example, you can create a hierarchical or tree‑based set of records, particularly if data volume fans out down the hierarchy or tree.

Don’t use this framework if:

- Creating or updating records requires immediate recalculation.

- Integration is challenging because external systems host primary data for record updates. (Consider pushing updated data to Salesforce with the Bulk API.)

With those practices in mind, let's review our requirements and start building.

Consider the problem statement:

Given a job that needs to run daily, check if certain records meet pre-established criteria for further processing. If they do, kick off those processing jobs. Processing records might mean pulling data from multiple external systems to perform calculations. Steps in jobs should notify people via Slack that processed records are ready for review. Steps should also escalate notifications to managers and higher-ups in the role hierarchy based on a configurable delay after the first round of notifications.

This problem involves several different steps, some of which can happen independently of each other. There are many ways to split up the work. Here’s one grouping:

- The scheduler.

- The step interface and concrete implementations that process records (regardless of the type of processing).

- The processor that organizes steps.

- The Apex Invocable called by the scheduler.

- The notification piece. We use the Apex Slack SDK.

- There’s some complexity hidden in the phrase “configurable delay.” We'll review this complexity later on in this article.

Here’s an opinionated diagram for the built‑out framework:

Now, break down that diagram and start building the pieces.

Now, break down that diagram and start building the pieces.

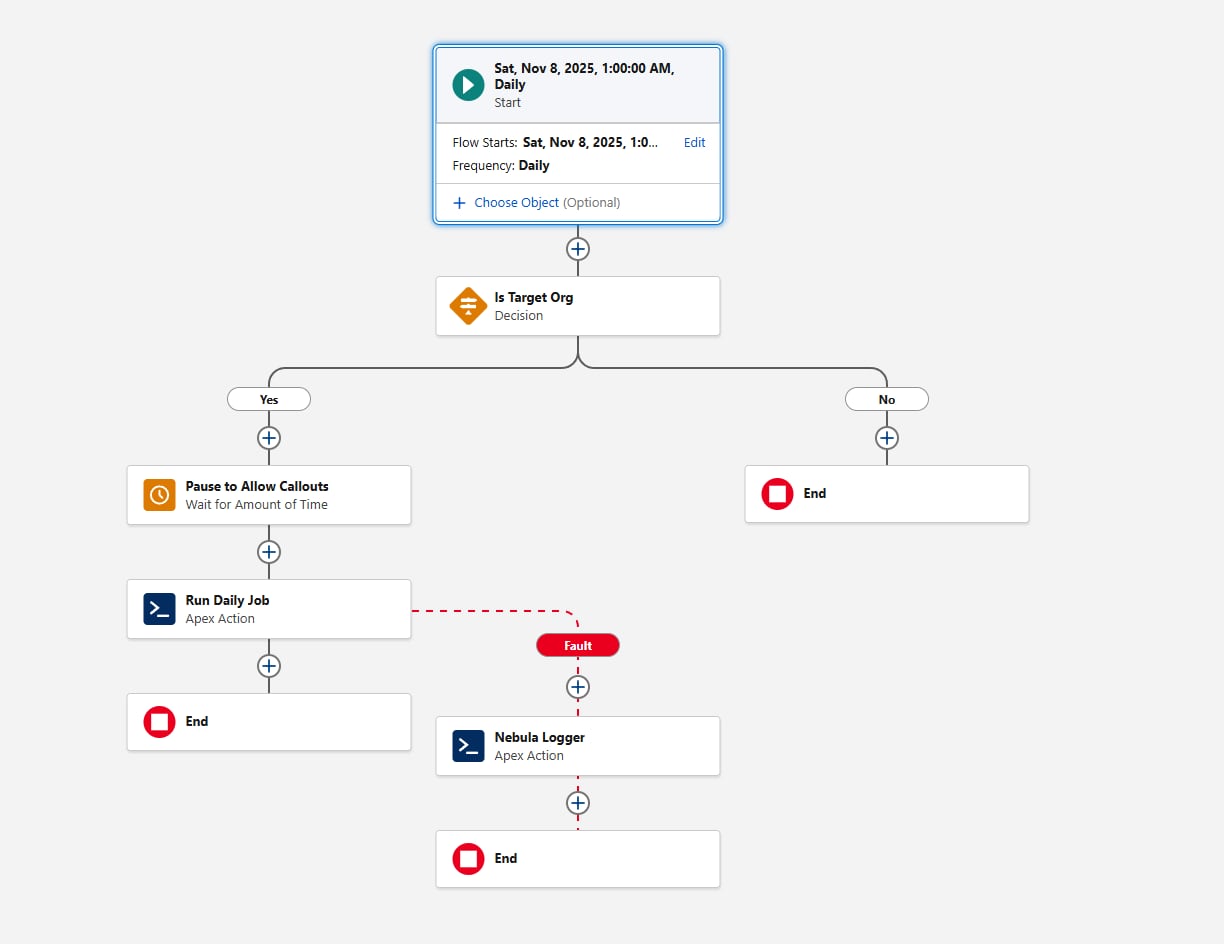

Scheduled Flow offers several advantages as a scheduling mechanism:

- Scheduled Flows can be packaged and deployed as metadata. This isn't true for jobs scheduled via Apex (or via the Scheduled Jobs page).

- The Wait element is critical for frameworks that require callouts. By using it in Flow, callouts aren’t necessary in the Invocable portion of the framework.

- Scheduling granularity meets the requirements: the minimum interval for Scheduled Flows is daily. If you need a higher frequency (for example, hourly), reconsider Scheduled Flow for this requirement.

Another consideration when configuring the Scheduled Flow is environment gating. Before invoking the Apex action, add a Decision element that evaluates the {!$Api.Enterprise_Server_URL_100} variable. This ensures the job runs only in the intended environments, such as UAT and Production. This pattern is important because sandboxes are frequently refreshed or newly created during the SDLC, and without an explicit environment check, a Scheduled Flow could unintentionally execute in environments where the framework is not meant to run. Using the contains operator in the Decision element makes the setup resilient to future sandbox creations or URL changes.

Finally, consider how the framework should capture failures. Always add a fault path when Flow calls any Action; for example, you can wire faults to Nebula Logger’s "Add Log Entry" action. Nebula Logger writes logs to custom objects, so customers should be aware that log data consumes org storage — by default, logs are stored for 14 days within an org, and then cleaned up; this retention period is configurable. Nebula Logger also uses Platform Events to publish logs, so log entries are saved independently from the main data-processing transaction — this ensures failures are captured even if the primary Flow or Apex action rolls back. Customers should evaluate expected log volume and retention requirements when considering the addition of a logging framework.

Here's what the Flow looks like:

Let's move on to the first pieces of Apex code with the scheduling requirement now satisfied.

Define a Step interface:

For this article, the step interface is shown as an outer class for clarity. The framework itself is flexible — teams can organize the interface and its implementations using any Apex packaging pattern they prefer, as long as all Step classes reference the same interface.

There are a few things to note about the methods defined within our interface:

execute, though argument‑less at the moment, improves when we pass aStateclass (or interface) to orchestrate data between steps when order matters.getNamecould return aSystem.Typevalue instead of aString. The goal is to give the orchestration layer a way to log step names without exposing other properties.

Here’s the first concrete implementation to show how these pieces fit together. With one exception later, we recommend using Queueable Apex to implement asynchronous processing within Apex; Batch Apex is typically unnecessary (and @future methods are discouraged). Queueable Apex starts quickly and, with Apex Cursors, has many advantages over Batch Apex.

Apex Cursors offer a modern alternative to the traditional Batch Apex model. Similar to Batch processing, a Cursor implementation can fetch records in chunks (up to 2,000 per batch). However, Cursors allow multiple fetches within a single transaction, enabling significantly higher throughput for large-volume operations.

When adopting Cursors as part of this framework, teams should be aware of current testing and mockability limitations. Cursor behavior in tests may differ from production behavior, so it’s important to design test strategies that avoid relying on Cursor internals and instead validate orchestration logic at the boundaries. As the platform evolves, these areas will continue to improve, but the core guidance remains: Cursors provide higher performance and reduced orchestration overhead compared to Batch Apex for many use cases.

To define a clear boundary between the system-provided Cursor and your own code, we recommend creating a Cursor‑like representation when implementing the Step interface. Consider this code:

Notice the Cursor class. Apex cursors are instances of Database.Cursor, but our Cursor implementation gives us flexibility around the shortcomings of Cursors. Here’s the implementation:

For the rest of this article, we omit the sharing declarations when referring to Apex classes. In practice, ensure top‑level classes explicitly use with or without sharing to conform to your object model and permissions.

Also note that our Cursor implementation delegates to the platform Database.Cursor, with added benefits discussed next.

First, here are the corresponding tests:

By making Cursor virtual, concrete CursorStep implementations can operate without a Database.Cursor when they don’t need to iterate a large record set — similar to returning a System.Iterable<T> instead of a Database.QueryLocator in Batch Apex. Here’s an example:

Note that because this class is also abstract, it leaves the concrete implementation of innerExecute to subclasses.

There’s also an alternative to the CursorLike inner subclass. If you know concrete versions of a step like this won’t burn through other governor limits, you can return this.records from CursorLike.fetch and override the parent CursorStep.shouldRestart() to return false. That allows you to iterate over a list bounded only by the Apex heap limit of 12 MB per async transaction.

Our Cursor-based implementation gives us plenty of flexibility when paginating over large quantities of data. The Step interface, meanwhile, gives us the flexibility to describe and encapsulate steps of all sorts.

Consider a Flow-based step:

Because Flows can’t return output parameters that conform to an Apex-defined type, we check for a shouldRestart output parameter before using it.

Some steps might be feature‑flagged. You can implement logic to decide which steps to include, or use a no‑op step for a disabled feature. The Null Object pattern is a common way to reduce complexity within the orchestration layer:

We now have quite a few building blocks to work with. Let's look at the orchestration layer responsible for iterating over steps.

The processor is an inflection point in the architecture. We must decide who defines which steps get initialized, and where. Options include:

- Have the processor define which steps map to business logic. This option is simple, but it scales poorly for readability.

- Define the mapping with Custom Metadata (CMDT). Metadata Relationship fields don’t support

ApexClass, which loosely couples class name spelling into your business process setup. You can reduce admin risk by making the field a picklist and validating the type exists (Type.forName()or by queryingApexClass), but because CMDT records don’t support triggers, validation happens at run time. This route is testable, but admins can still create CMDT records only in production — proceed carefully. - Define the mapping with records. Non‑admins can configure steps, but deployments get harder and environments can drift. Proceed with caution.

There's a famous quote from Clean Code about how to handle this particular piece of complexity:

The solution to this problem is to bury the

switchstatement [for making objects] in the basement of an abstract factory, and never let anyone see it.

With that in mind, and because our current number of steps is well-defined and unlikely to grow too large, it's okay for the step processor to also be the factory for steps. This can use an enum to drive the switch statement:

And then for our StepProcessor:

The factory methods shown, like addTypeOneSteps(), can delegate concerns like feature flagging; cleanSteps() performs a one‑time check on the gathered steps to ensure that there aren’t any “empty” steps before going truly async. That might look like this:

We haven’t discussed error handling since mentioning Nebula Logger in the Scheduled Flow section. That’s because System.Finalizer lets us blanket‑cover logging for all error conditions without adding specific error handling in each step. Each Step focuses on running, while we log and rethrow any unhappy paths so they surface in unit tests. This supports safe iteration and production‑level alerting (using the Slack Logger plug-in for Nebula for all WARN and ERROR logs).

One note about error logging: passing the step instance into log messages assumes a level of trust in what becomes visible in logs. The default toString() for Apex classes includes all static and instance‑level properties in the message. That can be desirable — or it can leak sensitive information. While logging and security are not the focus here, note that for some systems, adherence to an interface like Step can also involve forcing an override for toString().

Such a method puts the onus on each object creator to decide what is permissible to print, which may be desirable.

On logging levels: at the StepProcessor level, we use INFO, the highest non‑error level. As you get more granular within the application, logging levels should decrease accordingly. Individual steps might use DEBUG for high‑level information, with FINE, FINER, and FINEST reserved for increasingly detailed output. Logging is as much an art as a science, but following these principles helps keep logs consistent and useful.

Before moving on, let's briefly reflect on the decision to have our step processor host the logic for which steps get used. In a large codebase, consider making StepProcessor virtual or abstract, and have subclasses identify specific steps to establish a proper separation of concerns.

The scheduler eventually invokes Apex. With the rest of the setup complete, the Invocable Apex section can decide which steps should run and pass the List<StepType> to the processor:

This is a simple part of the equation — using records, data, or logic to determine which step types to run. The Invocable Action is simple because we encapsulated complexity elsewhere. We’ve also protected against unexpected exceptions and made each piece easy to test in isolation.

The Apex Slack SDK is beyond this article’s scope, but one potential snag from the requirements bears revisiting: notifying people upward in the role hierarchy based on a configurable delay. On paper, this is simple, and you might (correctly) consider System.enqueueJob(this) in the StepProcessor. With System.AsyncOptions, our initial inclination was to use the enqueueJob overload to satisfy this requirement.

For now, however, the maximum delay via System.AsyncOptions.MinimumQueueableDelayInMinutes is 10 minutes. Because the requirement is 120 minutes, a few options remain. A naive approach might look like this:

In practice, the delay would be passed into this class because the delay is configuration‑driven.

We don’t recommend this approach unless you are certain there will only ever be one delayed notification type. It burns through 11 extra async jobs before starting (or more, if the delay increases). That cost might be fine for one job — not for many. You’d also need to add a method to the Step interface so each step can tell the processor how long to wait before restarting, which adds noise.

That leaves us with two interesting possibilities:

- You can slot the delayed step into your existing job framework if you already have a polling job scheduled at an appropriate interval. You should also be OK with the specified delay hitting up to 15 minutes later (15 minutes is the minimum refresh interval for an Apex-scheduled CRON expression). This roughly matches the Invocable Apex example; the scheduling is performed via Apex instead. In other words, you could reuse the same

Step‑based architecture to process records based on a “Start After” timestamp and decide which steps to use based on a picklist or multi‑select picklist mapping back to theStepTypeenum values shown previously. - Alternatively, if you’re comfortable defining an extra outer Apex class, fall back to Batch Apex (unlike Queueable Apex, which supports inner classes, Batch Apex classes must be outer classes) using

System.scheduleBatch().

Consider the Batch Apex example. While we generally recommend Queueable Apex for flexibility and control, this is one case where Batch Apex still reigns supreme:

And then, in the StepProcessor, imagine that the previously shown addTypeOneSteps() method is updated with this delayed step:

While we wouldn’t typically recommend this much hoop‑jumping, this step delay becomes another reusable building block. Until longer delays are allowed in Queueable Apex, it also represents the easiest way to produce this effect (without a polling mechanism, as discussed).

We’ve used object‑oriented design to fulfill the requirements and created a system that will scale while balancing the long‑term cost of building and maintenance. While step declaration and instantiation may ultimately outgrow their place in StepProcessor, there’s little additional technical debt here. With FlowStep, admins and developers can decide together when no‑code or pro‑code solutions make the most sense.

By using the System.Finalizer interface within Apex’s Queueable framework, together with Nebula Logger, we’ve built a robust, testable system that alerts us to unforeseen failures even if future steps lack explicit logging. For us, this system is happily crunching numbers and reducing cost and complexity. It has also given us valuable insights into Apex Cursors’ behavior under real workloads, helping us refine our approach while improving the feature itself.

By decomposing complex, high-volume workloads into modular execution steps, the Step-Based Asynchronous Processing Framework framework transforms platform constraints into engineered advantages, enabling predictable performance, observability, and governance at enterprise scale. Steps can be set up by both admins and developers, and in either case, step authors can safely focus on observing the basic platform governor limits (like DML rows, and query rows retrieved) without having to worry about how to scale each step.

To operationalize and adopt this pattern across enterprise implementations, architects should:

- Evaluate existing automations to identify areas where async orchestration can help improve performance and enhance observability.

- Break down large processes into discrete, independently executable steps with with clear processing goals and discrete author points (like Flow, or Apex).

- Define and group step types to accelerate step reuse and standardization across business units.

- Pilot the approach with new processes or existing automations. You might be surprised to find how many edge cases you find for free within steps, care of your built-in logging and observability!

James Simone is a Principal Software Engineer at Salesforce, and has more than a decade's worth of experience working on the platform. He was a Salesforce customer — and product owner — before moving into development, and has been writing technical deep dives about Salesforce since 2019 within The Joys Of Apex. He's previously published articles on the Salesforce Developer blog, and the Salesforce Engineering blog as well.